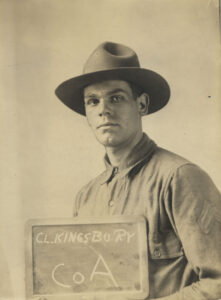

Chester Lyman Kingsbury

The Instrument of Character

In the winter of 1931, Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr. attended a “Takodah Pep Party” in the cooperative Keene & Cheshire County YMCA building on West Street in Keene, New Hampshire. His family had a long and important history with the local YMCAs, going back many years. That evening, County Y Director “Uncle” Oscar Elwell and his wife “Aunt” Frances shared their popular 16mm black and white films that promoted summer life at camp. They were pleased to see that it was Lyman’s time to enjoy a session spent benefiting from what his Father, a local toy company owner and philanthropist, had helped to build.

His older brother, Thayer, was also a Takodian. The die was cast.

The following summer, Lyman, or “Beany,” as he was typically called by his friends and family, played, painted, ran, swam, sailed, shot, and sang his little heart out. He was one of the very first 9-year old campers admitted to Takodah. Even at that young age, he learned to play reveille and taps on the bugle from a respected staff member named Rod Bent, a lesson that would set him up to play the trumpet in the years ahead.

It was a busy camping season as construction on May Lane, the road that now circles both “A” and “B” Fields, was started with Red May personally supervising the project. There were no reported cases of homesickness, a tribute to the excellence of the staff and overall focus on self confidence and new friendships. Dining Hall “Slingers” gave way to “Waiters” – a term that would stick for nearly 80 years – and Camp received use of a dumping truck from the Kingsbury family. Beany spent time working on the S.U.S (Shut Up & Shovel) Gang which used the truck to haul over 200 loads of gravel to build the tennis courts. They’re still in use today.

In 1933, Beany enjoyed a banner year at Takodah. They had record attendance, even in the face of the looming Great Depression. Campers had over 35 hobbies to choose from including making good use of the new Dark Room for photography. Woolcraft remained a popular activity for the staff and the “Bingling & Bungling Circus” visited that summer.

But that’s not all.

He also met plenty of new campers that session including Robert Douglas Lancey, a future friend and fellow veteran who would join Beany in making the supreme sacrifice in the Second World War.

When he wasn’t busy making the most of his time at Takodah, Beany was growing up with his family at 189 Court Street in Keene and summering at their cottage on Spofford Lake. In 1938, Beany started an impressive run as an honor student at Tabor Academy, located by Buzzards Bay, in Marion, Massachusetts. Their motto “All-A-Taut-O,” as they say, “makes Tabor students poised and ready for whatever may come.” And Beany would certainly make the most of whatever came at him during his time at the renowned private school. His senior year was the most impressive and he followed his brother through a wide range of activities and sports.

The class of 1941 saw the brothers in top-performing action. Thayer was class Vice President and Beany was Treasurer. The most important aspect of his job was to collect $13.35 from each senior! One late November night, Beany and Thayer worked backstage and proved they were “artists at heart as they paint each other and incidentally some scenery.” Nevertheless, “The Heritage of Wimpole Street,” a short play based on the family life of beloved nineteenth-century poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and acted by the Fairhaven High School thespians, impressed the local audience. The Kingsbury brothers further supported the Dramatic Club by starring together in a western thriller called “Murder in the Snow.” The gunfights were particularly exciting to rehearse and perform.

Thayer managed the baseball team with Beany playing the infield. The team struggled that year, but they still managed to have plenty of fun. Thayer was also Captain of the soccer team with Beany playing defense. Beany took a turn and managed the basketball team with “Captain Crocker” and “Coach Boothby.” That team also struggled but hit their stride later in the season with wins against Dartmouth High and the Tabor Alumni. Beany was a tough leader and notoriously gave the players “a talking to each time they weren’t in bed on time.”

As war intensified in Europe and US involvement became a distinct possibility, the “military year” at Tabor generated a lot of interest in the Rife Club. Thayer was president, of course, and Beany significantly advanced his skills using the two club rifles supplemented by personally-owned weapons. They made great use of the outdoor range but when it came to winter, they wanted to continue their practice. So, they built an indoor range in the basement of the study hall. There was also Flag committee, Glee Club, and sailing cruises in the Atlantic.

Beany masterfully played the trumpet in the Orchestra with concerts in November and December. They were a huge hit. He even played several Christmas parties and the band was noted to have had its “most successful season while playing a prominent role in school life.”

But, once again, that’s not all.

He was a Creative Writer at The Tabor Log weekly newspaper. As to be expected, Thayer was the business manager. Beany’s articles were popular “having been the product of long thought.” The staff was known for spending many hours clicking and clacking on typewriters far into the night. Beany went on to write for The Fore ‘n’ Aft yearbook as well. He worked hard to represent Tabor through the eyes of the students and was exceptionally proud of his work. He was voted “most versatile” and “brainiest,” seeing as he was on the Scholarship team. They were the “intellectual aristocracy of the school.”

It was clear that Beany adored his time at Tabor. He would look back upon it with great affection when he graduated in 1941 and set his sites on attending Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

His collegiate life was just as packed and impressive as was his high school years. When he wasn’t focused on his academics, he was a member of Phi Sigma Kappa, a family of leaders known as a “lifelong brotherhood dedicated to the betterment of the individual.” He wrote for the newspaper, played his trumpet in musical competitions, played soccer and was in the intramurals. In the summers, he worked at the family’s Toy Company back in Keene.

On June 26, 1942, after completing his first full year at Williams, he filled out DSS Form #1 and registered with the Selective Service at the Local Board No 11, 45 Main Street, in Keene. He was 5’7” tall and weighed in at 143 pounds.

He was 19 years old.

Beany never stopped moving and, by all accounts, had a privileged, accomplished, and impressive upbringing. The path was his to choose. The direction was his to make. The expectations were his to fulfill. Wherever his life would lead him, he’d surely take it for all it was worth. But there was a constant thought that remained close at hand for the young man who had the world within his reach. There was a reminder that maybe he could do more than take what he was given to him or get that which he had earned. There was a feeling that it was his turn to do his part for the nation and for the world.

War. It called to him the way it had called to his Father, who bravely served with the United States Army as a Corporal in the 101st Engineers Battalion, Company A, during World War One. Now, it was Beany’s turn to march for democracy and fight for freedom.

In February 1943, Beany traveled home to Keene to speak with his parents. They deliberated and debated the choice at hand: enlist in the Army or remain at Williams to finish his undergraduate degree. Of course, there was only one decision to make. It was the same decision being made my thousands of young men in homes across the country in those days.

Beany knew it. Chester knew it. Like father, like son.

On March 24, 1943, Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr. enlisted in the Army at Fort Devens in Massachusetts. After processing, he proceeded by train to Fort Eustis, Virginia where they follow the motto “nothing happens until something moves.” And Beany was always moving.

Fort Eustis, located in Newport News, VA, was established in 1918. It was a large, multi-purpose, military training facility for artillery and observation. It had also served as a prison, and a Works Progress Administration work camp. Beginning in the 1940s, Fort Eustis served as a Coastal Artillery Replacement Training Center, which included engineering and transportation training. Over 20,000 troops were trained at Fort Eustis during the Second World War.

A large Station Hospital was built to care for the soldiers – including Beany who was a patient for a week when he took ill that summer – which continues today as the McDonald Army Health Center. The installation was also an international training center for troops from the British Army’s Caribbean Regiment. When the war ended in Europe, there was an effort at the Fort to de-Nazify POWs. The program gave 26,000 Germans a six-day course in democracy in “the hope that they could return to spread democratic ideals at home.”

During his basic training, Beany was tapped to teach mathematics to his fellow soldiers due to his advanced proficiency in the subject.

After completing his initial testing and training on 28 October 1943, Beany, now Private First Class Kingsbury, proceeded to a “Service Command Service Unit” in New York City to participate in the Army Specialized Training Program (ATSP). Intended to provide specialized education for junior officers and enlisted technical specialists, the program focused heavily on math (algebra, geometry, trigonometry and calculus) but also included chemistry, physics, geopolitics, military science and writing skills. The workload was heavy, six days per week, and was intended to complete the equivalent of two semesters of work in just three months.

Henry Stimson, Secretary of War during World War II from 1940 to 1945 and self-professed “father of the ASTP,” wrote:

Each step of the ASTP story was tied in with the ups and downs in the Army’s estimate of its manpower requirements. In all such changes, the college training program, as a marginal undertaking, was sharply affected. [The choice was] between specialized training and an adequate combatant force.

The program also represented the spirit of “Taylorism,” of the scientific management approach that dominated the ‘New Deal’ programs of the Roosevelt Administration. Faced with the incredible task of expanding the Army from a few hundred thousand in the 1930s to the 8 million under arms by 1945, the Federal government applied standardized testing on a massive scale. Recruits were tested both to identify potential officer candidates, who had good leadership and managerial skills, as well as functional “human capital” analysis, where soldiers were sorted into groups defined by ability and potential job skills.

After beginning ATSP in New York, Beany’s aptitude saw him transferred to Massachusetts on 6 December 1943 to finish up the program at Harvard University in Cambridge where he was on the Dean’s List and ranked in the top five of his class. After graduation on 29 March 1944, Beany went home once again to inform his parents that he had received his orders. He was shipping out but, per Army regulations, he hadn’t been told where he was going. As he sat with the family and pondered the possibilities of what lay before him, he hoped and prayed that he would see his home again.

Beany would soon learn that he was assigned to Company L in the 101st Infantry, 26th Infantry Division. The 101st Infantry Regiment was an old organization, originally formed by Boston Irishmen during the Civil War. They were joined by the 104th Infantry, an even older formation with roots in the French and Indian Wars a century earlier, and the “new” 328th Infantry, which had been formed during the First World War. Given that most of the troops that had fought with the 26th in 1917-18 were from New England, the division was nicknamed the “Yankee Division.”

Beany felt right at home in the 101st.

He joined the division at the end of their formal training at Camp Campbell, Kentucky that summer before taking a train north to Camp Shanks, in Orangeburg, New York, arriving there in late August. Even though Beany had limited training, the division prepared for shipping out, moving to the port of New York on the 26th and sailing east to France in troop transport Argentina the next day. The troops disembarked at Cherbourg on 7 September and set up camp at the nearby Valognes Staging Area where they spent the month fitting out equipment and preparing for combat operations. This included weapons and vehicle maintenance, daily marches, combat skills, mine removal and first aid. They also incorporated the latest lessons-learned reports from the battlefield.

The more they were briefed, the more the reality of what lay before them rapidly set in. Beany would distract himself and his fellow soldiers by playing patriotic tunes and popular hits on the trumpet he had brought with him when he traveled from the US to France. It was his connection to home. It was a reminder of simpler times. It was a beacon of his personality. It was also a welcomed sound in the midst of carefully controlled chaos and the horrors of war.

But the time for Beany to put the trumpet aside and pick up his rifle once again would soon come to pass.

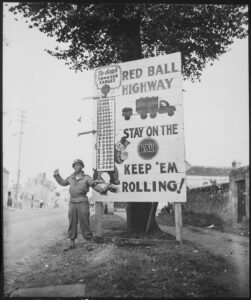

By mid-September, following the Allied breakout from Normandy in late July, German defenses in France had collapsed and the Wehrmacht had been pushed back into Belgium and south to Lorraine. Owing to the long distances, the front lines units were short of everything, with supply routes hundreds of miles long. Accordingly, almost 3,000 men of the 26th division temporarily formed 19 provisional truck companies and participated in the “Red Ball Express,” a huge logistical operation that delivered food, supplies and ammunition to the combat units at the front.

In early October the division, now assigned to XII Corps, shifted east to Moselle where they relieved the 4th Armored Division in the the Salonnes-Moncourt sector starting on 7 October, though the 10st did not arrive until the 16th. As the four other XII Corps divisions (two Infantry, two Armor) needed to refit and resupply following the heavy fighting in September, the 26th Yankee division maintained defensive positions in preparation for a major Corps-level offensive in November. The goal was Faulquemont, an important railroad junction about 20 miles to the northeast, which would clear the way to advance along the rail line to the Rhine river. The Yankee division’s task was to seize and hold the high plateau on the right flank, which would protect the Corps’ drive to Morhange and then Faulquemont. If they failed, enemy observation posts could direct artillery fire across the entire flank and rear of the American positions.

Failure was not an option.

Facing the 26th and defending the heavily-forested slopes of the Forêt de Bride et de Koecking was the 361st Volksgrenadier Division. Although a new formation, comprised of a mixture of Sailors, Luftwaffe personnel and other miscellaneous troops, they were led by veteran officers and senior enlisted. And, in contrast to many other German formations, they had enough horses to pull their entire complement of artillery, which formed a powerful series of batteries near Dieuze that would play a key role in the coming battle. The defenders were heavily entrenched, held the high ground and were favored by the weather – heavy rains and low-hanging clouds grounded American airpower as well as artillery observation planes. An officer from the 104th would later say that:

all through this I think we were taking a worse beating than the Jerries. They fought a delaying action, all the way. When things got too tough they could withdraw to their next defense line. And when we sat for awhile, they pounded us.

XII Corps did have their own advantages, however, and that was a tremendous superiority in artillery firepower. A key element in the American industrial style of war, U.S. artillery was technologically advanced and well supplied. On 8 November, the initial one-hour barrage stunned the front-line defenders and the 101st Infantry advanced quickly, seizing the Seille river bridge at Moyenvic and began climbing the slopes of the Cote Saint Jean, a long, slope leading up to a ridge (marked Hill 310 on U.S. maps) overlooking the Seille river. The German defenders regrouped, however, and supported by machine guns and artillery from the village of Marsal, opened a murderous fire, completely stopping the advance and pinning down the attacking companies for the rest of the day. Over the next three days, despite heavy rain, thick mud and well dug-in Germans, the 101st managed to maneuver around the ridge line, clear the villages of Morville-les-Vic and Salival and finally drive the defenders off the ridge.

The 101st was then ordered to advance along the south edge of the plateau, with the goal of taking the villages of Haraucourt-sur-Seille and St. Medard along the way. The task was made more difficult as the regiment was already understrength, the fight for Hill 310 alone had cost 478 officers and men, dead and wounded.

Starting on 12 November, the 101st and the 328th Infantry began clearing the sodden forest along the plateau. The advance was slow, owing to thick copses of beech and fir trees that provided good cover for the defenders, and heavy fighting took place around Berange Farm. South of the woods the 101st embarked on an attack to take Saint-Médard, but enemy artillery and machine guns caused heavy losses. As the hours rolled on, the fighting was even more bitter, with American armor gradually blasting the Germans out of the woods on either side of the main forest road. Losses were very heavy, both in the fighting and to the weather – the 328th evacuated over 500 men owing to trench foot and exposure in the first four days of fighting. The 104th was even weaker, some of its rifle companies averaged about 50 men instead of the normal 193.The 101st Infantry had just received some 700 replacements, but it would require time for so many new officers and men to learn their business. The Germans had also suffered heavy losses and they began to retreat, covered by artillery fire from Dieuze.

Finally, on 13 November, an ad hoc group of armor and infantry, including Beany, made a sweep through the Bois de Kerperche, a series of woods along the road to the village Guebling. Fighting was relatively light that day and Beany and his good friend Sgt. Charles M. Manwiller, a 29-year old sales clerk from Palmyra, Pennsylvania, sat in the woods near the small hamlet of Wuisse awaiting the order to advance. They were cold, hungry, and exhausted from a hard week of fighting their way through the frigid woods.

As they started to move towards the front of a large grove of trees, several shots rang out from a small group of concealed German soldiers dug in about 200 yards away. They were near Salival Farms on other side of Route 399 to Dieuze. It would have been impossible to spot them.

Sgt. Manwiller instinctively hit the deck to take cover. He tipped his helmet up and looked back over his shoulder to signal Beany to lay low and stay put.

It was too late.

PFC Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr. had been shot in the head by a sniper and killed. He lay face up, on his back, in the cold mud. Light snow and frozen leaves lay around his body. His rifle was at his right side. His helmet on the left.

He had been in France for just three months.

Sgt. Manwiller called for help and T/4 John L. Farrell, an Army medic who would go on to receive the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions that week, attempted to render aid, but there was nothing that could be done. Beany – a man whose melodious trumpet and exuberant nature had made so many tired soldiers smile – was dead, in the midst of battle, far from home, with no hope of rescue or resuscitation. After an Army Chaplain briefly prayed over Beany, the 26th had no choice but to keep moving for their day was far from over. T/4 Farrell pressed forward, initially hesitant to leave Beany’s body unattended to. But he had to keep his attention focused on the men who were wounded. The men he could help. The men who were still alive.

Later that day, T/Sgt. Clifford Walker, commander of PFC Kingsbury’s platoon, surveyed his men and realized Beany was missing. He talked to T/4 Farrell, who recounted the story of locating the body. T/Sgt. Walker then passed the news along to 1st Sgt David F. Jennings, who filed the paperwork that would eventually lead to the Kingsbury family being notified that Beany was missing and had been killed.

Several hours later, after the sun had faded from the sky over war-torn France, S/Sgt. Sam Gambacorto recounted the story of how he’d found a dead comrade. He’d been delivering rations and ammunition to the company earlier that day when he found his friend, Beany. He double-checked the dogtags just to be sure. He was right. It was him.

Sam was sorry to lose another buddy he had just barely gotten to know.

A few days later, with the plateau secure, the 26th Yankee Division regrouped, issued dry clothing and warm food to the men and received a few days of rest. They also asked for replacements to fill the holes left by their dead and wounded comrades and began preparations for the next attack.

The war still needed to be won before they could go home.

While the Kingsbury’s were told in early December 1944 that Beany was missing, it wasn’t until the following June that they were formally notified of his death.

It is with profound regret that I confirm the recent telegram informing you of the death of your son … who was previously reported missing in action on 13 November 1944 in France.

They were understandably devastated and the whole community was made aware of what had occurred. As letters of condolence and bouquets of flowers came pouring in at home and at the factory, it seemed that Beany’s loss echoed around southern New Hampshire.

It was also apparent that the loss had been felt across the world. In the summer of 1945, while still deployed in France, Sgt. Charles M. Manwiller sent the Kingsbury family a letter.

The day Chester was hit, he was right alongside of me and nothing in the whole war was harder on me, for Chester was like a younger brother to me.

Morrill Ross, Brigadier General, U.S. Army, Commanding, also wrote to the Kingsburys in 1945

I know only too well that words cannot bring comfort to your heart in these hours of loss. However., as your son’s division commander, I want to tell you that all of us who remain in this division grieve with you in the loss of our comrade. He did his duty splendidly and was loved and admired by all who knew him. We will not forget.

As they continued to come to grips with the reality that their beloved son had been killed in action, Chester made a pact with Winifred, Beany’s grieving mother, that they would ensure their boy was given the honors he deserved and placed into the family plot at Greenlawn Cemetery in Keene. The problem was that it quickly became apparent that the US Army did not know where Beany was. His body had not been recovered. His personal effects, including the prized trumpet, could not be located.

He had simply vanished into the confusion that comes from combat.

Chester, a loving and dedicated Father, wrote to anyone he could find that might help him track down his son and his belongings. He wrote letter after letter, month after month, year after year, pleading with the Army to find Beany. He couldn’t understand how they didn’t know what had happened or where he was. Chester made it a point to write the letters from his office so that his wife would be spared the pain contained within these communications.

July 12, 1945. “His personal effects have never been returned. We are particularly anxious for the return of a valuable trumpet which he had with him.”

July 16, 1945. “Can you advise us where he is buried and when he can be returned to the United States.”

On September 10, 1945, a large package arrived at the family home in Keene. It had been sent from Quartermaster Depot in Kansas City, Missouri. It contained one item, in a case, marked as “damaged.” When they opened the box, Chester and Winifred gasped and looked at each other with tears welling up.

It was the trumpet.

They finally had something back. They picked it up, held it together, and were overcome with thoughts of Beany playing it as he grew up and went off to war.

Chester now doubled his efforts and resumed his campaign of correspondence. The language in his letters became increasingly frustrated and desperate. It was tearing him apart.

November 1, 1945. “Will you contact his Company Commander, Junior Officers, and Chaplain and see if you cannot get some information for us in regard to his burial. I understand that the 26th Division is soon to return, and I sincerely hope you can get some details for us before the 101st is demobilized and contact is lost.

December 3, 1945. “If there is no information now after all these months, is there any chance that there ever will be? Will you please advise if we may expect to receive any further information?”

November 9, 1946. “We have received letters from three boys that were with him at the time he was hit. It was during an advance by his regiment and the territory was not at that time or later occupied by the enemy. This made it difficult for us to understand why there are no records as to his burial.”

November 27, 1946. “I do hope you will report any information that comes to light in the investigation, even if we do not get the thing we want most to know.”

In every response, usually sent back in a very short amount of time, the US Army tried to help Chester understand the reality and complexities of combat and the aftermath of war. They reassured him they were doing everything they could to find his son. But what Chester didn’t know was that during an investigation by the Search and Recovery Teams of the American Graves Registrations Service in April 1946, they recovered the remains of a deceased solider from Section 1, Plot 1, Grave 1 in the French Civilian Cemetery near the church in Wuisse. There were other Americans buried to his right and left, but they appeared to have been interred for a longer period of time.

The remains, then designated “Unknown X-6089,” had been discovered by the Mayor Rene Peouve of Wuisse in January 1946 when he was out walking his dog along the perimeter of the town. It appears the body had never been disturbed. Rene then worked with several villagers to recover and bury the body in the church plot. They marked it with a simple wooden cross emblazoned with an star in the style of the American flag.

Until his discovery and burial, as it would later be determined, Beany had laid where he fell, facing the heavens, for 14 months.

The clothing and equipment identified the man as a member of the American ground forces but, at that point, he was still unidentified as a named individual. Among the articles recovered were remnants of a field jacket with a laundry mark “K-6918,” a helmet, a raincoat, a paybook, and a few photographs that appeared to show a girl’s face, an elderly couple, and a young lady with a man. There were no dog tags.

X-6089 (who we now know was Beany) was carefully exhumed, examined, and thoroughly documented by the American Graves Registrations Service in case a future investigation should be able to apply an ID. The remains were then transferred to the Lorraine American Cemetery, in St. Avold, France and laid in Plot NN, Row 10, Grave 119.

Beany rested in peace in the company of other heroes of the campaign in European theater.

Then, on 9 August 1948, Chester received the letter he had been anxiously waiting to read for several years. It had been sent by Lt. Col. T. H. Metz, a Quartermaster in the US Army Memorial Division.

There has been forwarded to this office a burial form for a deceased member of the Armed Forces, with certain identifying information which leads us to believe the remains are those of your son.

But Chester was still full of questions and frustration. His letters resumed.

September 7, 1948. “What explanation can you give us as to why the body (which had been positively identified during combat operations) was left to be found by a civilian two years later? What explanation can there possibly be with this information on record that our report was “MISSING IN ACTION” and yet was not until June of 1945 that we received word of his death?

After another year of back and forth communications, and after an extensive investigation by multiple post-war services using dental, medical, and divisional records, the US Army finally identified and verified the body of X-6089 as PFC Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr.

It was time to bring him home.

In July of 1949, Beany arrived in the United States after a long journey by truck, ship, and train. His remains were delivered to Floyd Huntley, a Funeral Director at Aldrich Huntley Funeral Homes in Keene. His belongings, including the photos he had with him at the time of his death, were delivered to the family home on Court Street.

After a service attended by clergy and community alike, Beany was buried, as planned, with full military honors in Greenlawn Cemetery.

Each Memorial Day, the family visits the grave to pay respects to their fallen warrior of the Second World War. In 2019, the family brought something with them that they have never brought to the graveside before. It’s an item that they had all this time but, after Chester and Winifred passed away, they never really understood what it was until its history was recently brought to light.

It’s an item that belonged to Beany and now, after 75 years, it is close to him again.

The trumpet.

Read the next story in the series.

Return to the Lost Takodians of WWII main page.

SOURCES:

- Kingsbury Family interviews

- YMCA Camp Takodah History, Oscar & Francis Elwell, 1971. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- YMCA Camp Takodah Registration Cards. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- Ancestry.com Records, Media, and Kingsbury Family Trees

- Tabor Academy

- Williams College

- Historical Society of Cheshire County

- Harvard University Archives, Harvard Library

- The Crimson, Harvard University

- Fold 3 Records, Media, and Military Documents

- Wikipedia

- YankeeDivision.com

- ibiblio.com

- Newspaper Archives

- Newspapers.com

- history.army.mil

- Keene Evening Sentinel

- Library of Congress

- Lane Memorial Library

- eucmh.be

- Individual Deceased Personnel File, Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr., National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO

- FindAGrave.com

PHOTO CREDITS:

- Kingsbury Family Photos

- YMCA Camp Takodah Photo Archives

- Wikimedia

- eucmh.be

- Lane Memorial Library

- Harvard University Archives, Harvard Library

- Individual Deceased Personnel File, Chester Lyman Kingsbury, Jr., National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO

- Google Street View

- Graeme Noseworthy, Personal Photos, 2019