Thomas Aaron Eaton

The Last To Fall

When Thomas Aaron Eaton was born on July 20, 1925, his parents, Thomas and Jane, were just 21 years old.

His father was a Night Watchman at the New England Gas & Coke Company in Everett, Massachusetts. His mother was a homemaker who took care of Thomas’s two siblings along with her mother and sister in law. While he was born in Keene, New Hampshire, Thomas was raised in a modest suburban home at 29 Hancock Street in Everett. He attended the local public schools where he gained a reputation of being smart, athletic, caring, and outgoing.

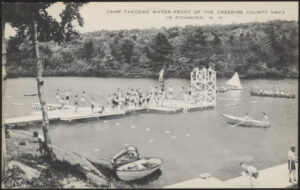

He was ideal for an environment that was specifically designed to be “friendly to all.” And so, Thomas came to YMCA Camp Takodah in three separate yet significant years.

In July of 1936, at the age of 11, Thomas was in Camp with 5 other boys who would go on to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces in World War II. They would all be lost in battles at sea, in the sky or on the ground all over the world.

While they were at Takodah, however, they happily made the most of what was offered to them. They used the new sailboats, the latest sports equipment, expanded athletic fields, a pristine lake, and so much more. They were a unique pack of brilliant boys who lived life to the fullest from Opening Campfire to Closing Candlelight.

Thomas took a year off in 1937 but, when he came back in 1938, he was one of the last campers to see Takodah before it was utterly devastated by the Great New England Hurricane. The property would practically be leveled when the category 3 storm arrived in the churning skies over Cass Pond late in the afternoon of September 21st, just a matter of a few weeks after Camp had wrapped up the summer season. The straight-line winds flattened over 200,000 square feet of hemlocks, pine, and hardwood trees. Buildings were smashed and the roads were rendered impassable. The water tower was ruined. The lake was choked with debris. The dock, a massive and heavy structure, had been picked up and tossed like a toy to the far side of the lake where it sat with the tower, chute, and diving boards still attached. Everyone who came to Takodah to see, survey, and help that fall were stunned by the extent of the damage that had nearly destroyed their beloved camp.

Through all of the chaos, however, Oscar Elwell, the longtime camp director, never lost faith. He noted the following in his damage report to the County Y Directors:

Takodah may have changed in physical features but we maintained the same loyal friendliness and excellent cooperation. We miss those beautiful hemlocks but will get more sunshine and develop a larger parade ground. Camp will look different to we old timers but you can be sure the changes may prove to be a great advantage.

Thomas may have taken the following few summers off to volunteer or work as the region went through the process of reconstruction after the hurricane. When he returned in 1942, he would have experienced a campus that was almost entirely transformed. He would have seen thousands of three-year old white pine seedlings that had been planted by hand, repaired cabins in new divisional configurations, a renovated waterfront, and an irregular tree line across the pond that looked absolutely nothing like he remembered.

And there were other changes as well. The leaders and staff had adopted new uniforms – white shirts and white trousers, shorts, or skirts – that would endure for decades to come. He met international staff members from China, Austria, and Japan. He hiked up Mount Monadnock and, for the first time, they “stayed overnight beyond the gate to the halfway house, climbed the mountain for sunrise, made breakfast, and hiked back to Takodah – a round trip of 30 miles!”

That summer Thomas also enjoyed “Army / Navy Day” which would eventually become the time-honored tradition called “Blue & White Day.” To mark the occasion, Frances Elwell, Oscar’s devoted wife and partner, “slipped out of camp and returned with ‘Tippy’ – a baby goat as mascot for the Navy.” The boys, including Thomas, contributed money to buy Tippy, who was given a lovely little home by Elsie Crowninshield’s nephew after the close of camp. The boys also gave to the July 4th Fund, China Relief, USO, YMCA Prisoners of War Fund, and for Takodah Restoration as the post-hurricane work continued year after year.

They were fueled by tradition and driven to service.

Back at home, Thomas continued to diligently make his way through school. He worked part-time as a Sales Clerk at a local store throughout his time attending Everett High School. As the U.S. involvement in the war dramatically intensified, Thomas felt the call to serve. He spoke to his parents about enlisting in the autumn of 1942. As he was only 17 years old, Thomas had to have his Father sign a parental waiver that proved he was fully aware and in supportive of what his son was doing.

On 21 November 1942, his father signed the form and just six days later, Thomas enlisted in the United States Navy in Boston, Massachusetts with the rank of Apprentice Seaman, V-6.

He was transferred to the Navy Training Station at Newport on 30 November for 12 weeks of indoctrination “basic” training. This would have included learning how to follow orders, obey the rules and in general learn how to work well with others. Life on a ship could be cramped, with almost no privacy, as well as dangerous. Understanding how to get along and obey the chain of command was critically important. A few days before he graduated from basic, his rating was changed from Apprentice Seaman to Seaman 2nd Class, demonstrating that he had not only survived his training, he had thrived within it. He also qualified as a Class C swimmer, hearkening back to his days of passing his swim classes on Cass Pond.

Thomas was granted leave from 17-24 February 1943 in which he likely returned home to spend time with his family in Everett. Like all parents, Thomas and Jane were outwardly proud to see their handsome son strut around the house in his uniform while internally feeling the fear that comes along with the reality of war and the worry for a loved one who could be placed into combat.

Once his leave was up, Thomas was transferred to Navy Armed Guard School on 27 February. These units were originally established early in the war as an attempt to provide defensive firepower to merchant ships in convoy or traveling alone. The constant danger from enemy submarines, surface ships, and attacking aircraft required a state of constant vigilance and the Armed Guard provided inherent anti-air and anti-surface gunnery protection to merchants ships. Thomas spent 4 weeks in ‘C’ school, where he started receiving specialized training before he was sent to the Armed Guard Center in Brooklyn, New York, on 27 March 1943 where he worked as a Captain’s orderly performing clerical work.

But it was not the work that Thomas truly wanted to do.

Withing a matter of weeks, he requested assignment to Navy College Training. The program’s academic goal was to produce officers, not unlike the Army Specialized Training Program, which sought to turn out trained personnel in fields including engineering, foreign languages, and medicine, which Thomas was particularly interested in. Graduates of the program, were expected, but not required, to become officers at the end of their training. Of the 25 men who passed screening tests, Thomas was ranked number 5. As part of the application process, the Navy requested transcripts of Thomas’s records from Everett High School on 11 May 1943. Soon after, his request was granted and he was given permission to proceed.

Thomas took some well-earned leave at home from 15-31 May 1943 as he waited to begin his new training.

With the New England summer heating up in June, Thomas was transferred to the V-12 training program at the Navy Training Unit at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The primary purpose of the program was to “give prospective Naval officers the benefits of a college education in those areas most needed by the Navy.” But, the Navy did not want to interrupt the “normal pattern of college life,” so the participants were given a chance to complete a degree in their field of study; while supplementing their course work with Navy classes, for which the colleges awarded regular academic credits.

But, once again, it was not the work that Thomas wanted to do.

With his rating changed from Seaman second class back to Apprentice Seaman, Thomas left the program after a month and awaited new orders. In October, he was transferred to the Receiving Station in New York where he was reinstated as a Seaman second class. He started working a variety of jobs in the armory, including performing gun maintenance.

And yet, Thomas still was struggling to find the role where he could succeed.

Shortly before taking 11 days leave in late January, 1944, Thomas had an opportunity to work in the sick bay. He found the work to be professionally fascinating and personally fulfilling. He worked hard, which was noticed by his fellow sailors and superior officers. He repeatedly demonstrated a natural talent for working with the patients, doctors, and the careful application of a confident and reassuring bedside manner. This is critically important in patient care. His interest in medicine and caring, truly caring for people, came shining through.

That was it. It clicked. Thomas had finally found what he had been looking for.

Because of his efforts in the sick bay, he was promoted Seaman first class on 1 February 1944. He then passed a rating exam and was recommended for Hospital Apprentice first class on 14 March 1944.

The die was cast and Thomas put in the request to attend Hospital Corpsmen School. On his application he said:

My intention is to study medicine when I return to civilian life. I am greatly interested in the medical field and while in school specialized in general science and biology. I feel that I would be of greater service to the Navy as a Hospital Apprentice than a Seaman.

The Navy agreed and Thomas was sent to the school at the Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Maryland on 27 March 1944. Its mission was to develop, teach, and provide highly trained Hospital Corpsmen for the fleet: aboard ships, aboard Naval Hospitals, Department of Defense medical facilities, with United States Marine Corps units, or elsewhere as needed. The naval hospital that Thomas and 1200 other recruits worked in, was established as a 500-bed hospital to care for the center’s operating staff, recruits, students, and dependents, with provision to increase capacity to 1,000 beds or more.

Thomas’s hard work paid off and he was promoted to Pharmacists Mate third class on 19 May 1944. And now, it was time for him to transition out of training and get to work at Navy sites from the mainland United States to the far reaches of the Pacific.

The next day, 23 May 1944, Thomas took a train across the country to reach the Navy Hospital in San Diego. During the war, due to large numbers of casualties coming from the Pacific theater, the hospital rapidly expanded from its World War I layout. It now included most of the buildings in present-day Balboa Park.

The Balboa Complex, as it came to be called, included the main Naval Hospital which treated approximately 172,000 patients with a maximum occupancy of 12,000. It was a massive and very busy medical campus. Thomas would have marveled at the size, complexity, and clockwork like function of the operation. As he triaged men arriving stateside from places like Iwo Jima and Saipan, the physical and psychological treatment of men suffering combat injuries would have furthered strengthened his belief that he had found his right place at the right time within the Navy.

Thomas was briefly transferred to the Navy Training & Distribution Center in Shoemaker, California and then he was sent to the Headquarters’ company, First Base HQ, 5th Marines, San Diego on 11 September 1944. While there, Thomas trained as a combat corpsman to support Marine Corps operations in battle. He would have learned about trauma first aid, and the many types of wounds that modern weapons such as explosive shrapnel and high-velocity bullets inflicted. He also provided routine medical care to Marines injured in training or normal operations. And while Thomas missed out on the Okinawa campaign in April 1945, he almost surely was in training for the unprecedented amphibious landings planned for Kyushu, Japan, in October of that year.

But then, like a bolt from the blue, came news of one, then two, atomic bombs dropped on Japan. And then, to the shock of all, came the news of Japanese surrender. The war was over. Everyone would live. They could all go home.

Well, most everybody. While the tremendous armies, navies and air forces began demobilizing and disbanding at the end of the war, a relatively small force would remain in place to ensure the peace. And since the Navy gave demobilization priority to men who had served in combat or overseas, Thomas was not allowed to demobilize and was required to fulfill an additional year of his contract.

In late August, 1945, Thomas learned that he was being deployed overseas. After making preparations, receiving the appropriate gear, and sending a series of letters home to inform his family on what he was doing and where he was going, Thomas boarded a troop transport vessel and sailed to the Navy base hospital #18 on the distant island of Guam.

He arrived on 24 September 1945, just a few weeks after the formal surrender of Japan. Even though the war had officially ended, there was still so much to be done to finish the job. Thomas immediately got to work caring for injured service members as he assisted in the demobilization effort. He also had opportunities to provide medical care for the local population, including the elderly and sick children.

Thomas also endeared himself to the locals, learning the language of the Chamorros, the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands, in just a few months – an incredibly short amount of time – so he could provide superior care while understanding and respecting cultural sensitivities. Thomas quickly became a local celebrity, of sorts, as word spread of the charming American who could treat the kids by day and join the adults at the fiestas, or “gupots” as they are called, in the evenings. He would impress the locals with his athleticism by competing in feats of climbing and strength against the native men. They adored his wide smile, charming nature, and genuine interest in taking care of people. He had a feeling that this was where he was meant to be.

Thomas, the young, bright boy from Boston, had left his country, traveled halfway around the world, and found himself on the other side. And, as it would turn out, he would find even more than that.

While working at the hospital, Thomas met a local nurse named Catalina Taitingfong. She was a beautiful and intelligent Chamorro woman originally from the village of Yona and Thomas, who was one year younger than she was, fell for her almost immediately. As they explored the island and attended the gupots together, he learned that when the Japanese occupied Guam in late 1941, her family had suffered horrendous treatment. Catalina was part of a group of Chamorro nurses that had been forced to work under Japanese doctors and supervisors. While local interpreters were provided, and occasionally a Saipanese interpreter came around, it was exceedingly difficult and they were often terribly mistreated. After the island was liberated in 1944, Chamorro women were trained as nurse-midwives by the U.S. Navy to assist with home births on Guam. Chamorro children born on the island until 1967 were most likely to have been delivered by one of these nurse-midwives, including Catalina.

These women, known in Guam as “pattera,” played a unique role in Guam’s history and culture.

As Thomas and Catalina fell in love, his work at the hospital also continued and he set himself to the task developing new medical skills and techniques. Once again, the Navy took note of Thomas’s efforts and he was promoted to Pharmacists Mate second class on 7 November 1945.

At this point, Thomas’s military experiences and new found love had changed the game for him. With his enlistment due to end soon, meaning he’d be sent stateside and then home to be officially discharged, he formally requested an extension of enlistment for 3.5 months as “I desire to stay in the Naval Service until my 21st birthday, at which time I am to receive my discharge from the U.S. Naval Reserve, for the purpose of going into business here on Guam.” Based on comments Thomas made in letters supporting this request, it appears that he wanted to eventually become a pediatrician and go into private practice so he could continue treating the local children and the support native communities.

He also wanted to remain where he was so he could marry the love of his life. Catalina.

In December of 1945, Thomas learned two things. He was being transferred to the U.S. Navy Military Government hospital #203 on 28 December and that Catalina was pregnant. Thomas was elated even though he was unsure how he would support them after he was discharged. Nevertheless, his life and goals had fundamentally changed. He had a new mission to meet.

About a week later, Thomas was taken ill and became a patient himself as he stayed at Base hospital #18 for treatment from 23 April to 3 May 1946 after which he was returned to duty.

With his rank of Pharmacists Mate second class reinstated on 10 May 46, Catalina’s healthy pregnancy progressing, and talk of marriage surrounding the couple, Thomas felt a renewed sense of purpose, place, and balance in his life.

The next day, 11 May 1946, after being given a liberty pass, Thomas went to an afternoon gupot celebrating a patron saint. He entertained his native hosts during the sea-side party by out-climbing a larger, faster coconut tree climber in one of the good natured competitions on the island. As usual, they were all impressed with the young man and his funny accent who came to Guam from a place none of them had ever seen, let alone heard of. After enjoying his time off, Thomas started back to base. But the road had no streetlights. It was rough and winding. The moon was not full. The vehicle had limited headlights and no seatbelts. To make matters worse, Thomas was likely exhausted from working a long shift at the hospital and then thoroughly enjoying his afternoon off engaging in physical feats instead of getting some much-needed rest.

Around 7:15 PM, on Route 4, near Inarajan, Guam, Thomas’s jeep ran off the road and hit a palm tree. He was ejected from the vehicle and struck his head. While he briefly survived the impact, Thomas Aaron Eaton died within a few minutes. An accident investigation would later determine that even though rescue crews arrived on site only a few minutes after he crashed, there was nothing that could have been done to save Thomas’s life.

After the family had been notified of his passing by telegram shortly after the accident, they received a letter dated 31 May 1946 from Vice Admiral Louis Denfeld. It read, in part:

I know what little solace the formal and written word can be to help meet the burden of your loss but in spite of that knowledge I cannot refrain from writing to say very simply that I am sorry.

Soon after another letter arrived indicating that Thomas had been buried on 18 May 1946. It listed his location at the Army, Navy, Marine Cemetery on Guam as “Grave 12, Row 44, Plot 4.”

As the family pondered what to do and how to bring Thomas home to be buried in Everett, they received yet another letter from Chaplain Lt. (jg) J. Hailluer dated 3 June 1946.

The eventual return to this country of overseas dead of all services has been authorized by law and the entire task will be accomplished by the War Department, as soon as caskets can be procured in sufficient quantities. However, the scope of operations is world wide and will proceed area by area. At this time no estimate can be made as to the time of removal of remains from cemeteries in any given area.

They had no choice but to wait as the War Department was responsible for repatriating the tens of thousands of men that had died in places all over the world. He’d come home, eventually, but it would take some time. Thomas, the father, briefly considered going to personally retrieve his son’s remains and then realized that he had to be patient. He had to wait.

In the meantime, Catalina, having lost one of the great loves of her life, gave birth to a beautiful little boy, named Thomas, after his Father, in August 1946. While he and Thomas would never have the chance to know each other, she could see the resemblance and knew that they would have been close as Thomas, the father, was never, ever short on love or caring. Catalina would go on to marry another man and live a full life, eventually passing away in in Riverside, California in 2003. Thomas, the son, who would end up also taking the surname of his adopted Father, Lavoie Thomas, lives in the United States but has gone back to Guam from time to time to visit the place where his story ultimately started.

Back in the states on 30 October 1946, the Eaton family received notification that Thomas had been posthumously awarded the WWII Victory medal.

Over a year later, after letters were exchanged, and the appropriate paperwork filed, Thomas’s remains were disinterred on 3 December 1947. He was transferred to the U.S. Mausoleum in Saipan, where Thomas was prepared, placed in a casket and sealed on 14 February 1948. He was then trucked to AGRS port, Saipan on the 15th and transferred to U.S. Army Transportation ship Walter W. Schwenk, on the 26th.

Thomas was shipped to Fort Mason, San Francisco, where he arrived on 22 March 1948. He was then transported by rail the next day to Schenectady General Distribution Depot in New York where he arrived on 16 April. He was then shipped – with a military escort – on Train #64, New York Central Railroad, departing Albany 9:27 AM on 22 April and arrived at Boston South Station at 2:20 pm same day. Thomas’s was then transferred to the J.E. Henderson Co. Funeral Home in Everett, Massachusetts.

His journey was complete. Even though Thomas had loved Guam and wanted to remain there to build a life, business, serve the people, and care for Catalina and their baby, he had finally come back to where he was from. After a brief service, Thomas was buried in Glenwood Cemetery and his headstone was approved on 16 June and shipped to John F. Corbett, Superintendent of the cemetery, for immediate placement.

It is still in place today.

In one final note the Eaton’s received on 3 June 1948, they learned that Thomas had been posthumously awarded the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign medal and a Good Conduct Medal.

That last one was earned, in part, because of what he had learned not just in the service but in his heart, in his love, and at his camp.

Thomas was the last of the twelve Takodians of the Second World War to fall in the line of duty. While other campers most certainly served, the loss of these men would be felt around the world for many, many years to come.

Return to the Lost Takodians of WWII main page.

Author’s Letter – J. Graeme Noseworthy, Vice President & Historian, Takodah YMCA

Author’s Letter – Senior Chief Petty Officer Timothy L. Francis, United States Navy

SOURCES:

- Interviews with Thomas Thomas

- YMCA Camp Takodah History, Oscar & Francis Elwell, 1971. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- YMCA Camp Takodah Registration Cards. Takodah YMCA Archives.

- “The Whistling of the Winds and the Transformation of Camp Takodah” – YMCA Camp Takodah Blog, Graeme Noseworthy, 2017

- Ancestry.com Records, Media, and Eaton Family Trees

- Fold 3 Records, Media, and Military Documents

- Official Military Personnel Record, Department of the Navy, National Personnel Records Center, National Archives, St. Louis, MO.

- Wikipedia

- Naval History and Heritage Command

- Newspaper Archives

- Newspapers.com

- Keene Evening Sentinel

- FindAGrave.com

PHOTO CREDITS:

- Thomas Family Photos

- Historic Everett Archives

- YMCA Camp Takodah Photo Archives

- Wikimedia

- cnic.navy.mil

- Military Yearbook Project

- Naval History and Heritage Command

- American Battle Monuments Commission